Summary

Map of Philippines

The Philippines, a large archipelago country in the South Pacific, is a constitutional republic with a presidential system. Democracy was restored in 1986, but recent presidents have eroded human rights and rule of law, including principles of accountability and transparency.

The Philippines, under Spanish colonial rule for more than 300 years, established the First Philippine Republic in 1899 at the end of the Spanish-American War. President William McKinley, however, imposed US administration by force, precipitating a three-year guerilla war. Due to ongoing conflict, the US Congress granted Philippines self-administration and autonomy in 1916. It became a commonwealth just before World War II. Occupied by Japan in 1941-42, the Philippines was liberated by US military forces in 1944-45 fighting alongside a Philippine resistance army. The Philippines gained full independence in 1946, instituting a constitutional democracy. In 1972, Fernando Marcos declared martial law and imposed a repressive dictatorship for 14 years. The 1986 People Power Revolution forced Marcos from power and re-established constitutional democracy.

The 1987 Constitution, adopted by plebiscite, establishes a presidential system with a bicameral legislature. Presidents are limited to one term. Freedom House has ranked Philippines in the “partly free” category since 2005 due mainly to issues of accountability, transparency and rule of law as leadership swung between less corrupt and more corrupt administrations. Recently, under President Rodrigo Duterte from 2016 to 2022, and now under Ferdinand Marcos, Jr., Freedom House ratings dropped markedly.

Freedom House has ranked Philippines in the “partly free” category since 2005 due mainly to issues of accountability, transparency and rule of law as leadership swung between less corrupt and more corrupt administrations.

The Philippines is made up of 7,107 islands and is the 72nd largest country in the world in total area. The population is 110 million. The largest and most inhabited islands are Luzon in the north and Mindanao in the south. Ethnicity is highly diverse but a large majority of Filipinos are Catholic (85 percent). Five to ten percent of the population is Muslim. The Philippines was among the fastest growing economies in the world in the 2010s and was ranked 40th in the world in nominal GDP in 2022 ($401 billion in total output) by the International Monetary Fund. Gross National Income (GNI) per capita ranked 129th at $3,600 per annum, indicating a high level of income disparity.

History

Origins

Ferdinand Magellan landed in the Philippines in 1521 and claimed the islands for Spain. In 1565, Spain formally declared the Philippines a colony

The first inhabitants on the islands of the Philippines arrived approximately 30,000 years ago from Borneo and Sumatra. They are considered the ancestors to aboriginal Filipinos. Other settlers arrived from Indonesia (the Nesiots), southern China (Austronesians), and Malaysia, among other regions. Initially, Philippines tribes formed city-states (known as barangay) comprised of freemen ruled by a chief. In varying degrees, many barangays were subjugated to different Indian and Bornean empires in the first millennium. Starting in the 13th century CE, the Chinese Ming Empire dominated the island chain. In 1380 CE, the first Islamic missionary arrived on the southern Philippine island of Mindanao.

Spanish Conquest

“Magellan’s Cross” in Cebu where Magellan ordered a cross erected is commemorated as the place where inhabitants were baptized by Spanish missionaries.

Ferdinand Magellan landed in the Philippines in 1521 and claimed the islands for Spain. In 1565, Spain formally declared the Philippines a colony after defeating the army of the King of Cebu, a major island. The Spanish conquered Manila (also today’s capital) on the island of Luzon in 1570–71. Subsequently, King Phillip II sent large numbers of missionaries to convert the population to Christianity and to teach Spanish, which was imposed as the official language. Under Spanish rule, the Philippines became an important trading center, particularly Manila due to its favorable harbor. The Philippines, however, remained largely agricultural. Slavery and peonage were introduced in Spanish-controlled estates known as encomiendas.

Wars and Independence

Filipino leaders declared independence and formed the First Philippine Republic in January 1899. President William McKinley, however, refused recognition and imposed a US administration by force

Spanish colonial administration weakened as its empire collapsed over the course of the 19th century. When the United States declared war on Spain in 1898 in support of Cuban independence, US troops fought Spain in all of its remaining territories, including Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines. Spanish forces had already been driven from key positions due to Filipino insurrection and withdrew fully from the archipelago in mid-1898. As part of the Treaty of Paris ending the Spanish-American War, the U.S. paid Spain $20 million for the island territories.

Filipino leaders declared independence and formed the First Philippine Republic in January 1899. President William McKinley, however, refused recognition and imposed a US administration by force, allowing only limited self-government. Over three years, US occupation forces fought brutally against an insurrection. There were more than 200,000 deaths from conflict, famine and disease.

The Japanese Imperial Army invaded the Philippines in 1941. Troops and tanks moving on Manilla in January 1942. The islands were liberated in 1944-45 by an indigenous army fighting side-by-side with US forces.

The Philippine-American war formally ended with a Peace Proclamation in July 1902. But hostilities with guerilla forces continued until 1913, when President Woodrow Wilson declared the US government's intention to grant self-government. The Autonomy Act of 1916 passed by Congress established an elected national assembly for the Philippines. In 1935, it became a commonwealth, but any process for full independence was interrupted by the 1941 Japanese invasion.

The Philippines was liberated in 1944-45 with an indigenous army fighting side by side with US forces to defeat the Japanese. After heavy lobbying, Filipino leaders convinced the US Congress to grant formal independence in 1946. The Philippines declared full sovereignty and established a constitutional democracy.

Independence and Dictatorship

President Ferdinand Marcos, nearing the end of his second elected term, imposed martial law in 1972 and established a personal dictatorship. The September 24 Sunday issue of the Philippines Daily Express.

Free elections were held in the Philippines without interruption from 1946 until 1972, with a wide range of political parties competing for power. Politics, however, was dominated by the competition of political clans. High levels of corruption, a high concentration of wealth, and ethnic conflict prevented the development of strong democratic institutions.

In 1972, nearing the end of his second term, President Ferdinand Marcos imposed martial law and a new constitution to stay in power. He imprisoned political opponents, restricted liberties, and established a personal dictatorship lasting 14 years. During this time, he and his wife Imelda continued a pattern of corruption established in his first two terms. They plundered 5-10 billion US dollars and encouraged a general culture of corruption.

The ”People Power” Revolution

In 1972, nearing the end of his second term, President Ferdinand Marcos imposed martial law and a new constitution to stay in power. He imprisoned political opponents, restricted liberties, and established a personal dictatorship lasting 14 years.

In 1981, as a precondition for a visit by the Pope, John Paul II, Marcos lifted martial law. He held a new election under controlled conditions to gain a third elected term, which he had extended to six years. But the lifting of martial law opened space for political activity. Support for the opposition grew after the 1983 assassination of its most prominent leader, Benigno Aquino, especially as evidence emerged showing the murder was committed on Marcos’s orders.

In early 1986, Marcos called a snap presidential election before his third term was up to try to shore up power. By an improbable margin, the government electoral commission declared Marcos the victor. An independent electoral observation group (NAMFREL) held a parallel count, however. It determined that the united opposition candidate had won with 52 percent of the vote. Massive demonstrations broke out in support of the opposition’s candidate, Corazon Aquino, the wife of the slain opposition leader.

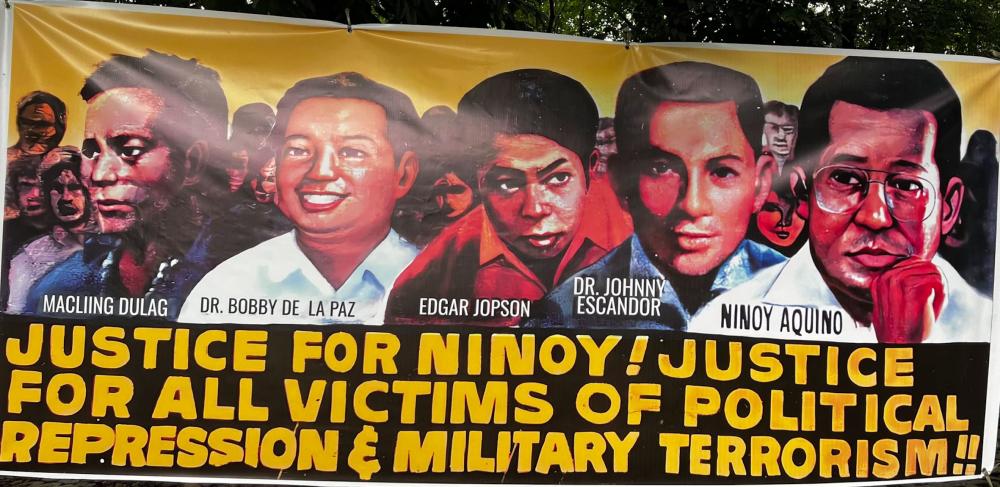

Benigno (Ninoy) Aquino’s murder in 1993, among one of several opposition leaders murdered as seen here in a mural, catalyzed popular support behind the opposition movement to Ferdinand Marcos’s dictatorship.

The People Power Revolution has stood as a model worldwide for how citizens can take back their government from a dictatorship through non-violent means. It is celebrated as a Philippines national holiday.

Marcos ordered the defense minister and head of the police and armed forces to suppress the demonstrations. They resigned and declared support for Aquino. As military units defected to the opposition, two million people filled the streets to demand recognition of Aquino’s election victory. Rival inaugurations were held on February 26, but top officials from the US government, which had previously backed the regime, publicly encouraged Marcos to accept defeat and resign. He and his family fled the country.

The People Power Revolution has stood as a model worldwide for how citizens can take back their government from a dictatorship through non-violent means. It is celebrated as a Philippines national holiday.

Accountability and Transparency

The issue of accountability and transparency in the Philippines is interwoven with its post-independence history and especially the struggle to overcome the Marcos dictatorship (see above). Under its restored democracy, accountability and transparency mechanisms were written into the Constitution and laws but the Philippines has had a mixed record of addressing ongoing corruption, abuse of power and other issues.

A new constitution, which was passed by plebiscite in 1987, retained a US-style presidential system with a bi-cameral legislature (a system originally adopted in 1935). The constitution also restored an independent judiciary and guarantees for human rights and media freedom. To prevent further abuse of power, the presidency was limited to a single six-year term and the power to impose martial law was limited to a sixty-day period. The bi-cameral legislature is elected every three-years for all 299 members of the House of Representatives and half of the Senate, whose members serve six-year terms. The legislature has powers to adopt laws and to impeach officials.

The recent presidential administration of Rodrigo Duterte (2010-16) and now of Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. have seen a return to more authoritarian-style rule.

The Marcos dictatorship left an embedded culture of corruption at all levels of administration and entrenched repressive practices in both the police and the army (evident especially in dealing with ongoing separatist insurgencies). After two generally successful presidencies, the next president was forced from office due to corruption. His successor became mired in a series of corruption scandals of her own and faced three impeachment proceedings. The presidency of Benigno Aquino III, from 2010 to 2016, attempted to reduce corruption and police and army abuses (see below).

Due to ongoing issues of accountability and rule of law, the Philippines has been consistently categorized as “Partly Free” by Freedom House since 2006. The recent presidential administration of Rodrigo Duterte (2010-16) and now of Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. have seen a return to more authoritarian-style rule, with a dramatic drop in scores in civil liberties and political rights (see Current Issues).

Democratic Rebirth

President Corazon Aquino, who led the opposition coalition in the 1986 elections, oversaw the Philippines’ democratic rebirth. In a plebiscite, the new Constitution passed with 77 percent of the vote in 1987. But Aquino struggled to reduce corruption within government, as well as to quell insurgencies in the south and north that first began in the 1960s and 1970s.

Corazon Aquino led the opposition movement as the presidential candidate in the 1986 snap elections. The People Power Revolution ousted the dictator Ferdinand Marcos when he attempted to steal the election through fraud.

With a new one-term limit under the Constitution, Aquino broke with her own Liberal Party to endorse Fidel Ramos as the candidate of Lakas-National Union of Christian Democrats (Lakas means “people power”). Ramos’s defection under Marcos had ensured the success of the 1986 revolution (see above). He also foiled several coup plots against President Aquino serving as her military chief of staff and defense minister.

The 1992 election showed clear weaknesses in the new constitution. The first-past-the post-system allowed Ramos to win the presidency with just 23 percent of the vote against five opponents. As well, his running mate for vice-president, elected separately, lost. Nevertheless, Ramos’s administration gained popularity by enacting economic reforms and achieving tentative agreements to end the communist rebellion in the north and an Islamic rebel movement in Mindanao in the south.

Corruption vs. People Power II

The next administrations were less successful and showed how easily both corruption and lack of transparency could impede democratic progress.

Joseph Estrada, elected president in 1998, was forced to resign in 2001 when a second People Power movement mobilized against his corruption.

Joseph Estrada, an actor-turned-politician who had won the vice presidency in 1992, led a coalition of conservative parties to run for president in the 1998 elections. He won with 40 percent of the vote. As in 1992, his running mate for vice president lost. Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, a member of a prominent political family and head of Lakas-NUCD, won the vice presidency.

Estrada's tenure as president was marked by high inflation, heightened insurgent violence, and rampant corruption. In October 2000, the General Prosecutor indicted Estrada on a wide range of crimes, including taking bribes, profiting from illicit gambling, and plundering the state coffers. He was impeached by the House of Representatives. When the Senate trial panel refused to consider crucial evidence — indicating an acquittal — another People Power movement rose up.

In January 2001, two million people again filled the streets to demand Estrada’s ouster and he resigned under such pressure. For the second time in 14 years, a popular movement against a corrupt leader brought down a government, showing again that citizens could hold leaders accountable.

A Sunshine Coalition

For the second time in 14 years, a popular movement against a corrupt leader brought down a government, showing again that citizens could hold leaders accountable.

Estrada was succeeded by Vice President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, who put together a governing coalition in Congress with two other parties, the National People's Coalition and the Liberal Party. But Arroyo’s Sunshine Coalition divided when she chose to run for president in the next election in 2004 after previously pledging not to take advantage of the exception for a one-term limit. She was elected to a full presidential term with a plurality vote of 40 percent. Her Lakas party also won a plurality of seats in the House, but the party split between Arroyo’s supporters and those of former President Fidel Ramos, who opposed her candidacy.

Sunshine Turns to Political Storm

Arroyo then proposed amending the constitution to re-create a unicameral parliament, end mid-term elections and eliminate presidential term limits. The reforms split the Lakas party further. Ramos, joined by Corazon Aquino, led opposition to the changes as a blatant power grab. The constitutional initiative foundered as Arroyo herself became embroiled in scandal. Tape recordings surfaced in which she was heard ordering the head of the election commission to commit election fraud in the 2004 elections. The affair led to large protests and two impeachment proceedings in 2005 and 2006. But both ended in Senate acquittal for lack of a two-thirds vote.

Then, in 2007, the president’s husband and other political allies were accused of taking large sums to lobby the government to award a Chinese company over a Philippines one for a broadband contract. In the midst of the new scandal, Arroyo pardoned and freed former President Estrada, only recently convicted for his corruption. The House of Representatives impeached her a third time, but the Senate failed again to convict, indicating the weakness of impeachment as a means of accountability.

A Return to Reform

In 2010, Benigno Aquino III, leader of the Liberal Party, won the presidency with 42 percent of the vote against five candidates. He pledged to end corruption and restore confidence to democratic institutions. His candidacy was propelled by the public mourning after the death of his mother Corazon Aquino in August 2009. Millions of people came to honor the leader of the People Power Revolution.

A commemorative stamp of the presidency of Benigno Aquino III, son of Corazon and Ninoy Aquino. He acted to regain public trust in elections. Shown here taking the oath of office in 2010.

President Aquino III acted to regain public trust in elections. A new head of the election commission automated registration and voting procedures and took other actions to prevent fraud. He also acted against corruption: he renewed the powers of the Office of Ombudsman and the Presidential Anti-Graft Commission; he increased the budget for the judiciary to take up a backlog of corruption cases; and he set up an independent Truth Commission to investigate the Arroyo administration. It found that she conspired to steal money from the National Lottery and that she diverted government funds intended for storm victims to private companies. (Arrested in 2012 on the corruption charges, her conviction was reversed on appeal to the Supreme Court in 2017.)

In 2013, the Commission on Audit revealed the breadth of government corruption by detailing the misuse of public funds intended for development projects by members of Congress. Thirty-one Congressmen and other officials were arrested in 2014. (The fund itself was later deemed unconstitutional.)

Elections Bring Mixed Results

Benigno Aquino III’s Liberal Party was given a solid majority in the May 2013 mid-term elections in both the House of Representatives and the Senate — the first time since 1986 that a single party had controlled both houses.

Despite this mandate, the elections indicated the staying power of a number of elite political families, usually supported by wealthy businessmen. Imelda Marcos, several Marcos relatives, former President Arroyo, her relatives, and other dynastic politicians from different regions were all returned to the Congress. Joseph Estrada, the corrupt former president, was elected mayor of Manila.

Then, in May 2016, the Philippines took a fully new turn. Rodrigo Duterte, the mayor of the Philippines’ second largest city, Davao City, won the presidential election with 39 percent of the vote. During his 20-year tenure as mayor, Duterte was renowned for “toughness” in dealing with crime, meaning a high level of police repression. (Human Rights Watch documented 1,000 extrajudicial deaths in Davao City in this time.) In the campaign, he pledged to address the country’s problems of crime, corruption and insurgency with similar “toughness.”

Current Issues

The 2016 presidential election winner, Rodrigo Duterte, carried out his promise to address crime with “toughness.” He instituted wide-ranging police dragnets against drug users and dealers throughout the country’s major cities. The level of police violence was startling. The government itself reported that between May 2016 and May 2022, the Philippine National Police and Drug Enforcement Agency had killed 6,252 individuals in drug operations. The UN’s Office of High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) put the figure of extra-judicial killings at 8,663. Human rights groups put the figure killed in Duterte’s “drug wars” at triple that number.

The 2016 presidential election winner, Rodrigo Duterte, carried out his promise to address crime with “toughness.” He instituted wide-ranging police dragnets against drug users and dealers throughout the country’s major cities. The level of police violence was startling.

Police and drug enforcement agencies claimed the killings were a result of armed resistance or attempts to escape, but independent media reported that most killings amounted to executions. There has been little accountability. Only one case was brought in court for extrajudicial murder.

The Philippines’ media operated under increasing government pressure and influence during Duterte’s presidency. In general, there is a thriving non-governmental media. But many media outlets are owned by businessmen currying government favor. Other media are targeted by the government with cyber-libel and general libel lawsuits (over 3,700 alone in 2022). In 2020, the country’s major independent broadcaster, ABS-CBN, was denied renewal of its national license renewed due to its critical coverage. ABS-CBN continues to operate regional broadcasts and an internet-based television and news service.

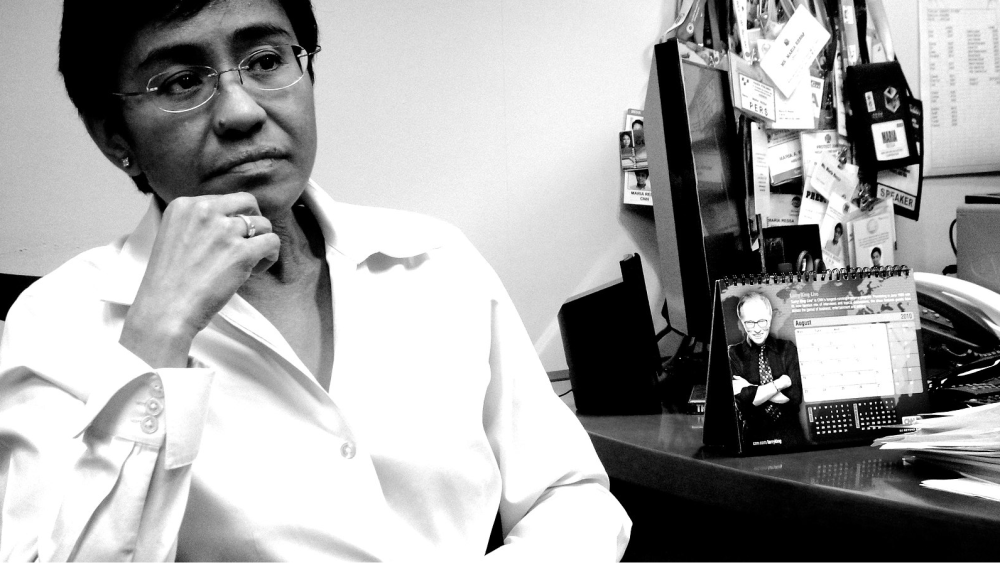

Maria Ressa, editor of Rappler, an online news outlet whose reporting on extrajudicial killings led to repeated political charges of “cyber-crime.” Ressa was co-awarded the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of the importance of independent media. Creative Commons License. Photo by Paul Papadimitriou.

One digital news outlet, Rappler was particularly targeted by Duterte for its reporting on extrajudicial killings and corruption. Maria Ressa, its founder and editor, was convicted of cyber-libel in 2021. She appealed the ruling but she and Rappler face other cyber-crime and tax evasion charges. In recognition of the importance of independent media, Ressa was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2021 along with the editor of an independent newspaper in Russia.

The Duterte government also used a practice called “red tagging” ─ naming people as members or collaborators with the Communist Party of the Philippines. Although the CPP’s armed wing has weakened and its civilian membership has fallen, the government continues to “red tag” journalists, opposition politicians, book publishers and NGO leaders, most of whom are not CPP members. “Red tagging” puts them under threat of government action and marks them for possible violent attacks by rogue militias.

Duterte, however, proved popular. The 2019 mid-term elections cemented Duterte’s hold in Congress, including full control of the Senate, with pro-government party candidates. As a result, there were few possibilities to initiate investigations of government corruption or policies.

Rodrigo Duterte, the mayor of Philippines’ second largest city, Davao, won the 2016 presidential election vowing “toughness” in dealing with drugs and crime. The UN’s Human Rights’ Office documented thousands of extra-judicial deaths under his presidency.

In 2022, several major figures of the People Power movement of 1986 died, including Fernando Ramos and Benigno Aquino III. A further indication of distance from the 1986 Revolution was the candidacy of Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, the son of the late dictator, in the 2022 presidential election.

Marcos, Jr. ran on a multi-video campaign of misinformation glorifying the period of his father’s rule and won with a decisive 58 percent vote against the Liberal Party candidate, Leni Robredo, who had served as vice president in opposition to Duterte. Robredo’s campaign was popular among young people, but she lost by large margins in most regions. Sara Duterte, who succeeded her father as mayor of Davao City, ran as Marcos’s vice- presidential candidate and won with a similar vote. They were sworn in on June 22, 2022 but in separate ceremonies in a sign of division between the political families.

The Philippines has a strong record of democratic elections since the 1986 Revolution toppled the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos, but the country has struggled to overcome Marcos’s legacy.

Marcos, Jr. made commitments to the UN to improve the human rights situation. But the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights issued its review report in September 2022 finding that violations had continued under his presidency. These included “harassment, threats, arrests, attacks, red-tagging against civil society actors, as well as continued drug related killings by police. . . . [A]ccess to justice for victims of human rights violations and abuses remained very limited.”

Among those red-tagged was presidential candidate Leni Robredo. Another prominent opponent of Duterte, former Senator Leila de Lima, has remained in detention since 2018 awaiting trial on fabricated drug charges. Two radio journalists critical of government policies were killed in September and December.

In January 2023, there was a rare victory for journalists with the acquittal of Maria Ressa on a tax evasion charge related to a foreign investment in Rappler. She still faces other charges and the cyber-libel conviction if lost on appeal.

• • •

The Philippines has a strong record of democratic elections since the 1986 Revolution toppled the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos, but the country has struggled to overcome Marcos’s legacy. Under the two most recent presidential administrations, offices that investigated corruption have either been dismantled or neutered. The increased power of political dynasties now limits space for opposition to compete in elections. Democratic institutions, such as an independent judiciary and legislative checks on power, have been weakened. Opposition political parties, civic organizations, trade unions, independent media outlets, and human rights organizations continue to exist and also continue to challenge abuse of power, but face ongoing intimidation and even repression.

The content on this page was last updated on .