Summary

Map of Uganda

Uganda, a country in Central Africa, is a unitary republic with a presidential system. The current president came to power in 1986 and has governed in an increasingly authoritarian manner.

Uganda was populated as early as 30,000-40,000 years ago BCE. In the modern era, it developed two major states, Buganda in the south and Bunyoro in the north. Following seventy-five years of Britain’s direct colonial rule beginning in 1894, the country gained independence in 1962 and established itself as the Republic of Uganda. A constitution was adopted the next year.

At first an electoral democracy, Uganda has had authoritarian governments since 1967. The worst period of rule was the murderous reign of Idi Amin from 1971–79. A milder dictatorship took hold in 1986 when Yoweri Museveni, a leader in the overthrow of Idi Amin, assumed the presidency. He has ruled ever since. While ending the worst repression, his “movement system” initially barred political parties. Since reinstating a multiparty system in 2005, Museveni ensured his power through unfree and unfair electoral conditions. Museveni gained an eighth five-year term of office in 2021. Opposition parties, civic organizations and independent media face an increasingly repressive atmosphere. Reporters Without Borders now ranks Uganda 133rd in the world in media freedom (a drop from 102nd since 2015).

At first an electoral democracy, Uganda has had authoritarian governments since 1967. The worst period of rule was the murderous reign of Idi Amin from 1971–79.

Uganda, including the area of Lake Victoria, is the 79th largest country in the world (241,550 sq. km.). It is bordered by Democratic Republic of the Congo to the west, Kenya, Tanzania and Rwanda to the east and South Sudan to the north. Uganda’s multiethnic population is 48.5 million (30th largest in the world), with an increase of 13 million since 2016. English and Kiswahili (Swahili) are official languages. By religious affiliation, 84 percent are Christian (39 percent Catholic, 32 percent Anglican, 13 percent other). Twelve percent are Muslim. The International Monetary Fund ranks Uganda 91st in the world in nominal GDP at $52 billion in 2023 total output. Nominal per capita GDP ranks worse, 160th in the world, at $1,163 per year.

History

Origins and Multiethnic Rivalry

Uganda was populated by hunting and gathering communities as early as 30,000–40,000 BCE. Different groups speaking Bantu, a major sub-Saharan African-language group, began residing in the area in the fourth century BCE and spread herding and agricultural practices.

The Nilotic speakers who stayed in Uganda formed two major states, Bunyoro and Baganda, and several minor ones. The major states were both ruled through a royal clan system in which clan elders elected the leaders (known as kabakas).

Cushitic-, Nilotic-, and Luo-speaking tribes, mostly pastoralist, migrated to the area from the west and north of Africa at the end of the first millennium CE. Some pastoralists moved further south to territories in current Tanzania, Burundi and Rwanda. The Nilotic speakers who stayed in Uganda formed two major states, Bunyoro and Baganda, and several minor ones. The major states were both ruled through a royal clan system in which clan elders elected the leaders (known as kabakas). Buganda, in the south, was the more successful in expanding its territory, making it the dominant state in the region.

Rivalry Ends in British Rule

Uganda thus had a system of rival states. When the British explorers John Speke and Henry Stanley arrived in the mid-19th century, they converted Buganda's kabaka, Mutesa I, to Christianity. His conversion sparked a competition among British Anglican, German Protestant, French Catholic and Islamic missionaries in the region.

In 1888, the British East Africa Company was granted full control of the whole Lake Victoria region but the company failed economically. In 1894, Britain made Buganda a protectorate with direct administration along with other East African States.

Buganda's Anglican and Catholic adherents combined to defeat Islamic converts, who had initially assumed central power. They then battled between themselves, with Protestant adherents victorious. The British, backed by Buganda’s military forces, then conquered Bunyoro and other areas. In 1888, the British East Africa Company was granted full control of the whole Lake Victoria region but the company failed economically. In 1894, Britain made Buganda a protectorate with direct administration along with other East African States.

The Road to Independence

During a large portion of colonial rule, Buganda had its own regional administration in exchange for loyalty to the Crown. When negotiations for independence began, Buganda's kabaka, Mutesa II, refused to make concessions for a unitary state. In 1953, the British negotiator exiled Mutesa II to London to force the issue but this only bolstered his standing among Bagandans. Mutesa II returned in 1955 with enhanced powers to appoint his own governing council.

In preparation for elections, the country's Catholics united in the Democratic Party (DP). Non-Baganda, non-Catholic groups formed the Uganda People's Congress (UPC), which was led by Milton Obote. But Mutesa II still opposed a unitary state and boycotted elections in 1961 for a National Assembly. A second election in 1962 was held in which the British governor agreed to Mutesa II’s demand for a set number of seats reserved for his Kabaka Yekka, or King Only, party.

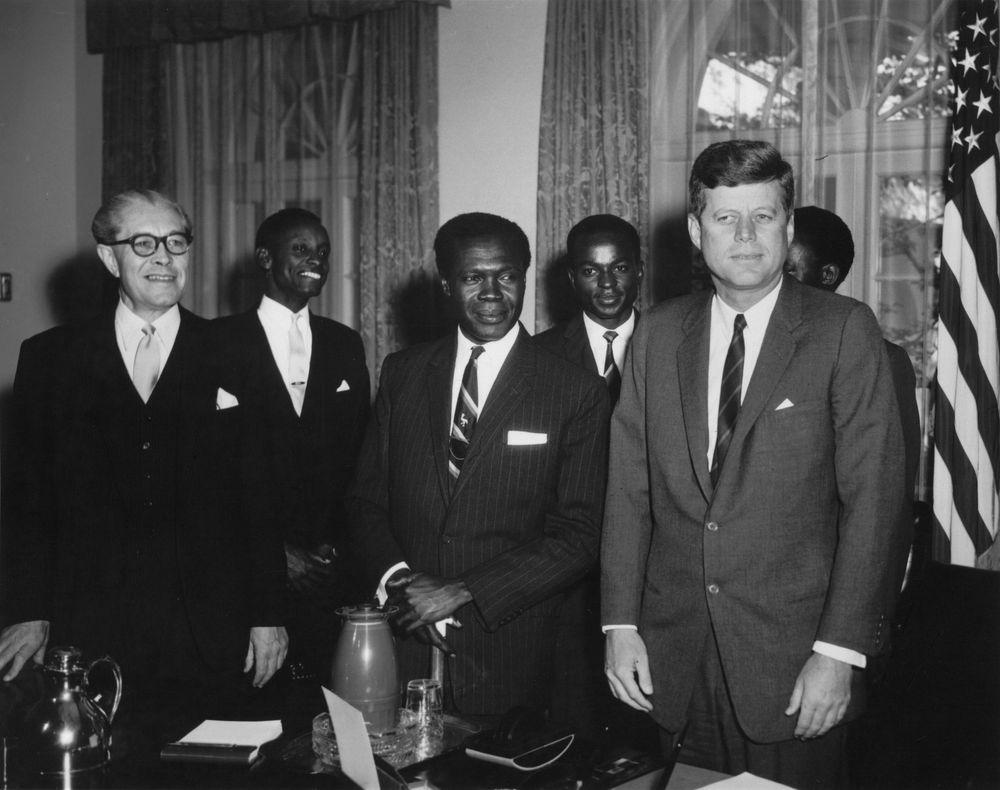

Milton Obote was elected Uganda’s first prime minister after independence in 1962. Above, Obote (center) meets US President John Kennedy in 1963 in Washington, DC. Obote ended the multiparty system with a new constitution in 1967. Public Domain.

Obote’s UPC allied with members of Kabaka Yekka (KY) to create a dominant two-party coalition leaving out the predominantly Catholic Democratic Party. The National Assembly elected Obote as prime minister and Mutesa II as president. A constitution adopted the next year made Uganda a federal republic with a parliamentary system.

From Elections to Dictatorship

At first, Prime Minister Obote managed the factions of his Uganda People’s Congress (UPC) and gained the loyalty of the army. He bolstered his position by enticing members of the KY to defect with state-appointed positions and by allowing residents of the "10 lost counties" of Bunyoro (territory Buganda seized in 1900) to return to their historical region by a referendum vote.

A new constitution in 1967 concentrated powers in the prime minister's office [and] Obote created secret police and paramilitary forces to keep control. Uganda’s early promise as an electoral democracy was put to an end.

A corruption scandal cost Obote support and he lost a no confidence vote. Instead of resigning, Obote carried out a coup against his own government with support of the military. He ended the multiparty system, deposed President Mutesa II and then forced him into exile. A new constitution in 1967 concentrated powers in the prime minister's office, got rid of the federal system, eliminated local and tribal authority and divided Buganda into four districts. Obote created secret police and paramilitary forces to keep control. Uganda’s early promise as an electoral democracy was put to an end.

Idi Amin's Reign of Horror

Over time, Obote feared the growing strength of a protégé who served as head of the armed forces. His name was Idi Amin. Before Obote could have him removed, Amin staged a preemptive coup in January 1971.

Idi Amin instituted one of the most repressive and deadly regimes in Africa's post-colonial history. Under his reign, Amin's forces killed more than 300,000 people

Idi Amin instituted one of the most repressive and deadly regimes in Africa's post-colonial history. Under his reign, Amin's forces killed more than 300,000 people, including mass executions of the Acholi and Langi ethnic groups for their presumed loyalty to Obote. In 1972, Amin expelled the entire Asian community (around 50,000 people, mainly Indians), thus removing Uganda's main class of commercial merchants.

Amin, who was illiterate, ran his government by oral orders, leaving no written records. But eyewitness accounts testify to the brutality of his rule (portrayed in the film “The Last King of Scotland”). Following a disastrous war of expansion launched against Tanzania, Amin was overthrown in 1979 by the Uganda National Liberation Army, a group of resistance forces led by Milton Obote. Saudi Arabia provided Amin refuge and he was never brought to justice.

"The Movement System"

Yoweri Museveni, leading the National Resistance Army, overthrew Milton Obote in 1986 after Obote returned to power. Museveni has ruled as president ever since. Shown above in a 2018 official portrait. Creative Commons. Photo by Reda Raouchaia.

Obote, still head of the Uganda People’s Congress (UPC), returned to the presidency through questionable elections held in 1980 in which the UPC gained a large majority in the National Assembly. (No other party accepted the outcome.) Obote's second period in office was a repressive repetition of his first. It ended in 1985 with a military coup ousting him from power. But the new military government faced a strong insurgent group, the National Resistance Army (NRA) led by Yoweri Museveni, a former officer in Obote’s intelligence service. The NRA seized Kampala, the capital, in January 1986.

Museveni installed himself as president. The first signs were promising. He ended the prior regime’s violence and adopted economic policies that helped Uganda overcome hyperinflation. But in a constitution adopted in 1995, Museveni had political parties barred to establish a presidential system. Only one “non-party” coalition called the National Resistance Movement (NRM) could compete in elections. Predictably, Museveni won the first two elections in 1996 and 2001, which were only nominally contested. The NRM won all seats in the National Assembly.

Under international pressure, Museveni re-instated a multiparty system in 2005 and allowed opposition parties. In conditions marked by limitations on voter eligibility, political intimidation, violence and electoral fraud, Museveni and NRM won the three following presidential and parliamentary elections held in 2006, 2011 and 2016 (see also Freedom of Expression below).

The Lord’s Resistance Army

[I]n a constitution adopted in 1995, [President] Museveni had political parties barred to establish a presidential system. Only one “non-party” coalition called the National Resistance Movement (NRM) could compete in elections.

Initially, the international community backed Museveni’s overthrow of Milton Obote. He gained international support due to his initial respect for human rights, adoption of IMF stabilization policies and efforts to reduce HIV infection rates from one of the highest to one of the lowest in Africa. The international community also strongly backed Uganda in its decades-long conflict with the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA), a terrorist movement led by a messianic warlord, Joseph Kony. He had split his guerilla forces from Museveni’s NRA and waged a civil war seeking to impose a theocracy based on the Ten Commandments. Captured by Ugandan authorities, he was released in 1992 only to resume warfare.

The LRA, known for gruesome practices, was successfully expelled from its original base in Uganda in 2005, but it survived in neighboring countries. Kony remains a fugitive from the International Criminal Court on war crime charges for his abduction and forcible use of children as fighters, among other practices. A 5,000-strong African Union army contingent, joined by US special forces, failed to capture Kony over many years. But the LRA was reduced to splinter groups and is no longer considered a threat by the government.

Joseph Kony waged a civil war to impose a theocracy in Uganda. A 2012 documentary brought international attention to Kony’s practice of press ganging children into his army. Posters of the documentary “Kony 2012” in Warsaw. Creative Commons. Photo by Mateusz Opasiński.

Despite aiding the military effort to defeat the LRA, the international community’s support for Uganda’s government diminished as Museveni adopted repressive means to maintain power and adopted harsh anti-homosexuality laws violating basic human rights of the LGBTQ+ community. Growing corruption also eroded confidence in the economy to slow foreign investment. Further description of Museveni’s rule is below.

Freedom of Expression

British colonial rule was less harsh in Ugandan territory than in other parts of Africa. A free media emerged as in other parts of the world. The Democratic Party, which united Catholic communities, even had its own presses. As dictatorship took hold of Uganda following independence, there was less respect for freedom of expression and none under Idi Amin’s murderous rule.

After Yoweri Museveni came to power in 1986, his government adopted a constitution guaranteeing human rights. Independent media was allowed to develop to an unusual degree for a semi-democratic regime. But in a new constitution adopted in 1995, Museveni ended the multiparty system and concentrated powers in the presidency.

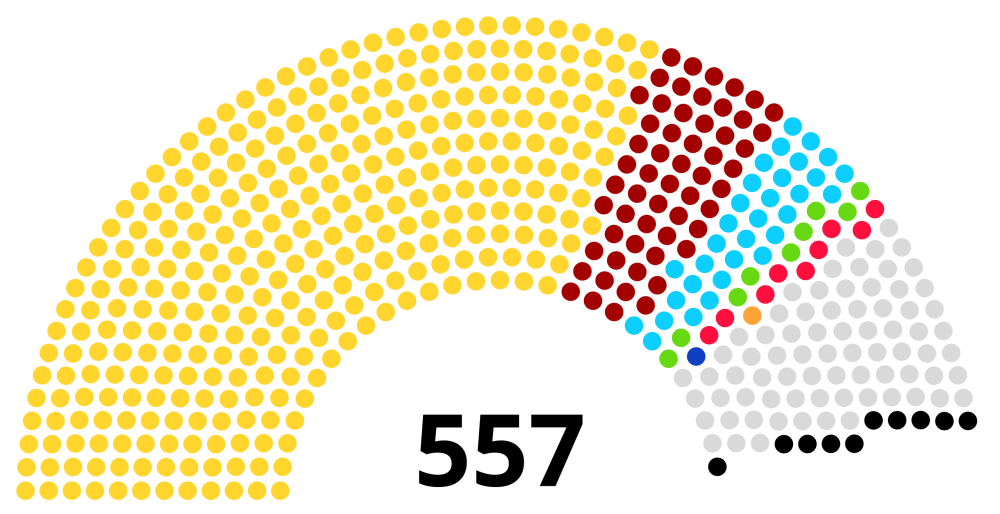

A multiparty system was restored in 2005 but President Yoweri Museveni’s National Resistance Movement dominates. As shown in yellow, it won 336 of 557 seats in the 2021 elections and has the loyalty of most independents. Public Domain.

As Museveni held onto power, his increasingly authoritarian rule put restrictions and government pressure on media, opposition parties, civil society organizations and social movements. A multiparty system was restored in 2005 due to international pressure, but the electoral system is heavily skewed towards Museveni’s National Resistance Movement, which dominates parliament. While freedom of expression still exists due to the persistence of independent media and civil society, it is under increasing threat. A detailed description is below and in Current Issues.

A Constitutional Guarantee

At first, President Museveni allowed a vibrant free media to develop following the Idi Amin dictatorship and repressive rule of Milton Obote. His second constitution adopted in 1995, which established a dominant presidential system, still included guarantees for human rights, including free expression.

At first, President Museveni allowed a vibrant free media to develop following the Idi Amin dictatorship . . . There arose more than 200 radio stations and 40 television stations, many with independent operation.

There arose more than 200 radio stations and 40 television stations, many with independent operation. According to a 2019 BBC report, 87 percent of Ugandans owned or regularly accessed a radio (73 percent listened at least once a week) and 34 percent owned a television (28 percent viewed at least once a week). Internet access was more limited. Only thirteen percent had access through cable by 2019, while 27 percent logged in to online platforms each week using WiFi.

Today, there are two major media holding companies: the government-owned Vision Group and the independently owned Nation Media Group (NMG). State-owned and influenced media dominate but independent media vigorously compete. The state-owned newspaper Bukkede has the largest circulation, at 33,000, while the largest NMG-owned newspaper, Daily Monitor, has 13,000. It and other independent outlets report on corruption, question government policies, challenge government abuse of power and regularly cover opposition parties.

Actual Government Practice

The legal environment, however, is only partly free and became more repressive as Museveni extended his rule. The Press and Journalist Act (PJA) require the registration of journalists and the licensing of media outlets. Both requirements are used to intimidate and control reporting. The Information Minister also issues regulations under the PJA on ethics and practices that tend to limit media freedom. All of these controls encourage self-censorship.

President Museveni and the government frequently threaten media outlets, sometimes closing them temporarily for reporting on opposition protests or government corruption.

President Museveni and the government frequently threaten media outlets, sometimes closing them temporarily for reporting on opposition protests or government corruption. There is frequent use of libel and defamation laws against journalists and editors, while other laws (such as the Anti-Pornography Act, adopted in 2014, and the Anti-Homosexuality Act, re-adopted in 2023) restrict referencing of sexual material and homosexuality. Arrests of journalists, often on false criminal charges, are frequent.

The internet is generally free but increasingly controlled for government purposes. Ahead of protests and elections, the Ugandan Communications Commission orders internet service providers to block media and social media sites to “prevent the sharing of information that incites the public.”

A Repressive Environment for Political Expression

The 2006 election, the first in 25 years to allow candidates from multiple parties to compete, were neither free nor fair. Kizza Besigye, the leader of the opposition Forum for Democratic Change (FDC), returned from exile to register in the presidential contest. He was then immediately arrested on false charges of treason and rape. Besigye was freed on bail but had to campaign without a court determining the lack of validity of the charges. In lengthy proceedings afterwards, Besigye was cleared of all charges in 2010.

Kizza Besigye, leader of the Forum for Democratic Change, ran and lost three times for president despite being under indictment and having organized vigilante attacks on his rallies. Creative Commons. Photo by Urban TV Uganda.

Conditions were clearly tilted towards Museveni and his National Resistance Movement (NRM). Electoral Commission members are appointed by the president. International monitors also documented restrictions on political party activities and voter eligibility; a strong pro-government bias in state media; use of government resources for Museveni and NRM campaigns; and electoral fraud. In the 2006, 2011 and 2016 elections, there were numerous police and vigilante attacks on opposition rallies and specifically on journalists covering opposition candidates.

Predictably, the Electoral Commission claimed decisive wins for Museveni and the National Resistance Movement in all three elections. Besigye and the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC) were the major opponents in each. Besigye’s highest vote was 36 percent. With a “first-past-the-post system,” the FDC’s best return was just over 10 percent of seats in the National Assembly.

Conditions were clearly tilted towards Museveni and his National Resistance Movement (NRM) . . . International monitors . . . documented restrictions on political party activities and voter eligibility; a strong pro-government bias in state media; use of government resources for Museveni and NRM campaigns; and electoral fraud.

After the 2011 elections, Besigye organized “walk to work” marches to protest electoral fraud and corruption. The marches, which demonstrated the large scale of his support, were violently dispersed. Nine persons were killed and there were widespread arrests. Journalists covering the events were again attacked by police and paramilitary groups.

For free media, there were constant challenges. For example, twenty journalists covering the impeachment proceedings of opposition leader Erias Lukwago in 2013 were arrested. The Democratic Party leader had been elected Lord Mayor of Kampala in 2011 and was impeached on a central government finding of corruption and incompetence. Journalists reported on the government’s lack of evidence. While Lukwago was removed temporarily from office, the High Court reinstated him. (Indicating the actual strength of the opposition, Lukwago won resounding victories in both the 2016 and 2021 local elections, which were less subject to fraud and unfair conditions.)

Campaign Against LGBTQ+ Rights

The government’s repressive campaign against homosexuality and advocates of LGBTQ+ rights has affected free expression. The government sponsored anti-homosexual demonstrations and campaigns against LGBT rights’ organizations. In 2011, and again in early 2014, a pro-government tabloid published the names, photographs and addresses of gay Ugandans. (A gay rights activist, David Kato, was murdered following the first publication of names.)

The Ugandan government has adopted increasingly harsh legislation against the LGBTQ+ community. The community has had international support, as above, at a London rally, but government repression has intensified. Creative Commons. Photo by Alisdare Hickson.

While laws against “sexual deviance” were already severe, stronger penalties were proposed in 2014 in the the Anti-Homosexuality Act (AHA) passed by parliament. Harsh sentences, including death, were included for homosexual acts. Criminal penalties were also adopted for promotion of homosexuality, including by the media. While the Supreme Court nullified the law on technical grounds, repression and discrimination of the LGBTQ+ community continued. (The AHA was then re-adopted in 2023. See Current Issues below.)

The government’s actions against LGBT rights, including police closure of AIDS clinics and organized break-ins at Ugandan NGOs, sparked international protests. Although the US continued military aid to Uganda to support capture of the international fugitive Joseph Kony (see above), in June 2014 then-President Obama approved economic sanctions on Uganda.

Current Issues

In the January 2021 elections, Yoweri Museveni again claimed victory with 58 percent of the vote against a new challenger. Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu, a singer popularly known as Bobi Wine, won 34.8 percent. Museveni’s National Resistance Movement (NRM) also dominated legislative elections, winning 336 of 557 seats in the newly expanded National Assembly despite receiving just 41 percent of the vote. Bobi Wine’s National Unity Party (NUP) earned just 57 seats in the “first past the post” system, while Forum for Democratic Change (FDC) won 32 seats. Other opposition parties won fewer than 10 seats.

The conditions again were both unfair and unfree. Covid 19 restrictions were used to prevent rallies of the opposition NUP and FDC, while events of Museveni’s NRM were allowed. As in previous years, the election campaign was marked “by violence, intimidation and harassment of opposition candidates and resources,” according to Freedom House.

In the January 2021 elections, Yoweri Museveni again claimed victory with 58 percent of the vote against a new challenger . . . Museveni’s National Resistance Movement (NRM) also dominated legislative elections . . . The conditions again were both unfair and unfree.

There were widespread arrests, including several times of Bobi Wine. The Uganda Communications Commission (UCC) ordered a five-day internet blackout as the election approached (internet access was restored only a month later). Journalists were frequently attacked for covering opposition rallies and a number were arrested. The voting total was skewed by lack of counting of votes. (The Electoral Commission admitted to not counting 1200 precincts from Kampala, an opposition stronghold.) The opposition NUP challenged the results in court but without success.

Still, the 2021 election campaign demonstrated decreasing support for Museveni and popular support for Wine. (See, for example, Resources for article on the film “Bobi Wine: The People’s President,” nominated for the 2023 Oscar awards.)

The situation worsened after the election. According to Freedom House, “Politically-motivated disappearances and reports of torture of opposition supporters in detention increased in the months after the election.” Wine claims that more than 3,000 NUP members were abducted by authorities. By government account, at least 31 of them were charged with serious offenses.

Above, a police officer chasing a journalist covering the rally of presidential candidate Bobi Wine in the 2021 elections, Opposition rallies were repressed, supposedly to enforce Covid 19 restrictions. Ruling party rallies were allowed. Creative Commons. Photo by Lawrence Kitatta.

To maintain power, Museveni and the NRM rely on their domination of all levels of government. Thus, supporting opposition parties means fewer chances for jobs, university placements, business registration or advancement of any type. The government also bribes and coerces opposition parliamentarians and supporters.

In 2019, the government issued a requirement for NGOs to provide extensive information to the National Bureau for NGOs on staffing, finances and activities. NGOs also had to register with the Personal Data Protection Office with minimal time for registering. In November 2022, 12,000 NGOs were closed for not renewing their registration or properly registering information, including human rights and LGBTQ+ organizations.

Ugandan intelligence officials also order the use of spyware on journalists, editors and NGO activists. Journalists and human rights activists continue to be attacked and arrested at opposition rallies and generally. Media outlets and NGOs have been frequent targets of police raids.

The government monitors social media platforms for signs of support for opposition. Content makers are now required to register and pay a $27 fee to post online. A new law, the Computer Misuse Act, makes sharing false or unsolicited information online a crime. As well, university classes are subject to ongoing monitoring by government officials, intimidating both professors and students and limiting academic freedom.

Despite the obstacles, independent media continue to be important alternative sources for news on corruption, other government malfeasance, government policies, maladministered development projects, opposition party activities and other news and issues.

Despite the obstacles, independent media continue to be important alternative sources for news on corruption, other government malfeasance, government policies, maladministered development projects, opposition party activities and other news and issues. Non-governmental organizations remain an important foundation for Ugandan civil society and a check on government domination.

In 2023, the National Assembly passed and the president signed a new Anti-Homosexuality Act that increased penalties for homosexual acts and relationships and other “deviancy.” The death penalty was introduced for “aggravated homosexuality.” Discrimination of the LGBTQ+ community remains common, as are police entrapment, arrests and attacks on those perceived to be a member of the LGBTQ+ community. The new law threatens a new health crisis and an undoing of Uganda’s progress prior to 2019 in reducing infection and deaths from HIV/AIDS.

The content on this page was last updated on .