The Origins of Human Rights

In Western thought, the concept of human rights is derived partly from the practices and texts of monotheistic religions such as Christianity, Islam and Judaism, as well as of other religions. While religion or religious authority were often used to justify hierarchical, monarchical, authoritarian and theocratic governance, it was also used to argue for human dignity, human rights and self-governance.

For example, one primary human right in all international conventions is the right to life — itself a commandment for human behavior in the Old Testament ("Thou shalt not kill"). Other ideas regarding human dignity, such as not to harm, injure or steal from others as well as precepts of justice and fairness, are all elaborated in religious texts that influenced and still influence the ethical beliefs — of the world.

[I]deas regarding human dignity, such as not to harm, injure or steal from others as well as precepts of justice and fairness, are all elaborated in religious texts that influenced and still influence the ethical beliefs — of the world.

The evolution of political freedom and the concept of human rights are drawn from many historical developments, including the expansion of citizenship rights for males in ancient Athens by Cleisthenes and Pericles; the abolition of slavery in the ancient Persian Empire by Cyrus the Great; and the Roman Republic’s establishment of citizenship rights for plebeians.

Another solid foundation was the Magna Carta, signed in 1215 by King John of England. It established more firmly ideas of constitutional limits, the rule of law and representative government in Europe. (The Magna Carta is discussed more fully in Consent of the Governed and Constitutional Limits).

The Early Enlightenment

The philosophical underpinnings of modern standards of human rights, however, are found in the Enlightenment, the historical period in Europe when concepts such as natural rights, natural law, social contracts and the rights of man were developed.

The philosophical underpinnings of modern standards of human rights . . . are found in the Enlightenment, the historical period in Europe when concepts such as natural rights, natural law, social contracts and the rights of man were developed.

Until the Enlightenment, most political philosophers justified monarchical rule. Thomas Hobbes, for example, famously defended monarchical rule as the only means to avoid the brutish state of man's nature. To monarchists, the tumultuous English Civil Wars of the mid-17th century confirmed their low assessment of human behavior.

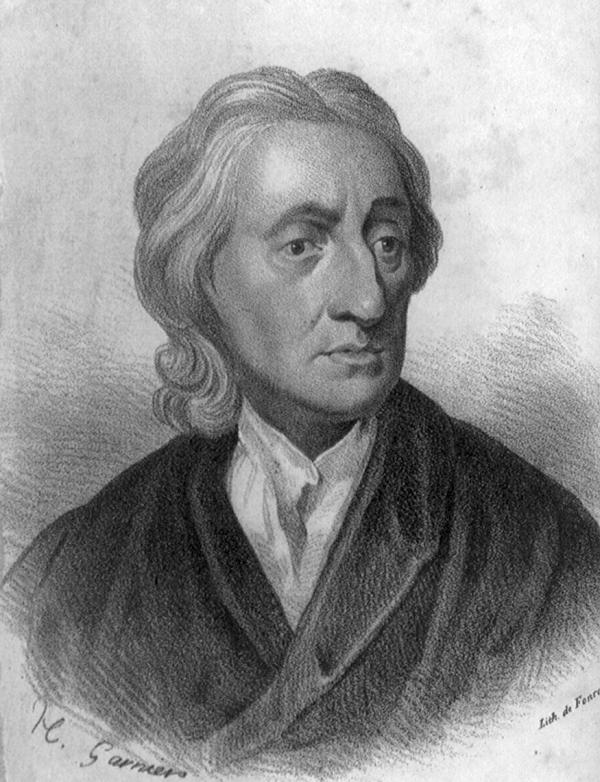

To republicans, it was the authoritarian actions of monarchs that made the fight for basic rights necessary. In response to Hobbes, the philosopher John Locke set out to find a new basis for legitimate government. In his Two Treatises of Civil Government, published in 1680 and 1690, Locke asserted that the essential aspect of man's state in nature is not brutishness nor lack of rationality but rather his possession of natural rights endowed by God. Most essentially, these are the rights to "life, liberty, and estate." In Locke’s view, people came together to form government not out of fear, as Hobbes wrote, but out of a rational self-interest to protect and enjoy their rights in common.

John Locke, above, was among the early Enlightenment thinkers. In The Two Treatises of Government, he asserted the natural or inalienable rights of “life, liberty, and estate” to argue in favor of forms of self-governance against absolute monarchy. An early portrait. Public Domain.

Locke was not the first person to assert a theory of natural rights, nor the first to develop a political philosophy of basic rights. (Examples date to the Classical period.) Still, he was the most influential thinker to posit that natural rights were the foundation for self-government among citizens. A government based on monarchy or one leader is tyrannical by its nature because it denies citizens the equal rights they possess from birth.

Locke’s philosophy had a great influence on the founders of the United States, and particularly Thomas Jefferson. His assertion in the Declaration of Independence of the self-evident nature of political equality formed the basis for consensual government — republican democracy.

From Locke to Kant

Out of the natural rights of man to “life, liberty and estate” proposed by Locke, there developed more expansive definitions of rights. The 1689 English Bill of Rights, influenced by Locke’s Two Treatises on Government, broadened the restrictions on state power developed from the Magna Carta to include an expansion of basic individual rights. These were rights that British citizens had established for themselves in their struggle with the Stuart kings. These included citizens’ rights to petition government for grievances, to be secure in one’s property and home, and to due process against abuse of power.

The US Bill of Rights, drawing upon Locke’s Second Treatise, went further by asserting affirmative political and civil liberties such as freedom of speech, association, assembly and religion. These, and the rights established in Great Britain, became foundational to self-governance (see also Constitutional Limits and Rule of Law).

Immanuel Kant, a later Enlightenment thinker, asserted that the human capacity for reason provided a basis for the universality of huma rights. A statue of Kant in his birthplace is in current-day Kaliningrad, part of the Russian Federation. It was previously Konigsberg, part of East Prussia. Creative Commons License. Photo by Valdis Pilskalns.

The 18th-century philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau was another major natural rights theorist. He argued for the abolishment of social distinctions and the universal application of political rights. His Second Discourse and The Social Contract influenced the adoption in 1789 of the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which embodied the more egalitarian spirit of the French Revolution.

Kant asserted that the human capacity for reason provided the basis for moral action. In this view, natural rights are not granted or given by God. They exist as human rights and are universal based on the underlying rationality of human beings and their capacity for moral action.

Soon after, the late 18th-century German philosopher Immanuel Kant revisited the issue of natural rights from a different perspective. He argued that universal rights and duties were not just inherent from birth or from the self-interest of individuals to protect their rights and possessions but also that they derived from the basic equality and moral autonomy of individuals. Kant asserted that the human capacity for reason provided the basis for moral action. In this view, natural rights are not granted or given by God. They exist as human rights and are universal based on the underlying rationality of human beings and their capacity for moral action.

One can cite many other philosophers in influencing the evolution of Enlightenment or liberal political thought, but these three — Locke, Rousseau and Kant — had the most profound impact in establishing the modern foundation for the respect of universal human rights.

The Struggle for Abolition

The English, American and French Revolutions did not establish full political equality, human rights or an end to state tyranny. There existed many contradictions between the foundational principles espoused in each of these revolutions and the practices of the governments they established.

The French Revolution’s assertion of human rights did not prevent the First Republic’s descent into the Reign of Terror in 1793. Mass imprisonment and thousands of beheadings were justified by the need to create a state of “virtue” to protect the revolution against all enemies. The Reign of Terror was ended by the National Assembly in 1794 but the Republic did not last long. In 1799, Napoleon overthrew the elected Directory as First Consul and then declared himself Emperor of a French Empire as he set about to conquer all of Europe.

Among the most significant and lasting contradictions to foundational principles of human rights was the practice of slavery.

Among the most significant and lasting contradictions to foundational principles of human rights was the practice of slavery. Notwithstanding the universality of his language, John Locke justified slavery or the right of “property in man,” as did other Enlightenment thinkers. What became evident, however, was that the abolition of slavery was necessary to establishing the universality of human rights.

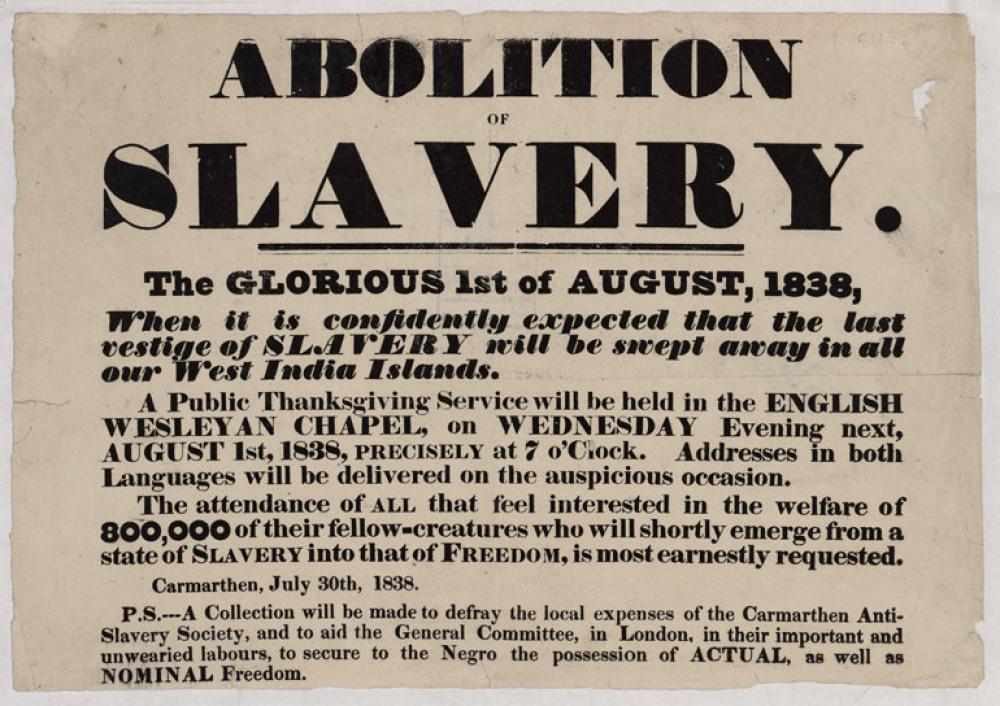

From the late 18th century, abolition movements struggled for the end of slavery and the basic rights of all persons regardless of race. Through the actions of abolitionists in the United Kingdom, a British High Court in 1772 declared that slavery had no basis in British law and thus on the territory of Great Britain. The British parliament outlawed the slave trade in 1807 and directed the government to end the slave trade by other states. In 1833, the parliament outlawed slavery altogether in most of the British Empire (although on a gradual basis providing compensation to slave owners).

A poster of the Carmethon Branch of the Anti-Slavery Society of Great Britain for a celebration of the final abolition of slavery in the West Indies on August 1, 1838, freeing 800,000 people. Public Domain. The National Library of Wales.

In the United States, the Continental Congress prevented the extension of slavery in northwest territories in 1787 and slavery was abolished in most northern states by 1808, although often by gradual means and often without establishing equal rights for free Blacks. The US abolished the international slave trade by law in 1808. But slavery remained an entrenched practice in southern states and expanded to new territories. Domestic slave trading flourished. By 1861, there were 4 million enslaved persons in 15 states.

The abolition of slavery in the United States and new independent states in the Western Hemisphere in the 19th century, along with the end of serfdom in Europe, led to the international recognition of one of the most basic rights: that of persons not to be held in servitude.

Despite the many efforts of the abolition movement in the U.S., slavery only ended as a result of the Civil War between the United States (the Union) and the secessionist Confederate States of America. President Abraham Lincoln's wartime Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863 declared enslaved persons in Confederate states “henceforth and forever free.” The 13th Amendment to the Constitution was adopted in 1865 abolishing slavery throughout the United States.

The abolition of slavery in the United States and new independent states in the Western Hemisphere in the 19th century, along with the end of serfdom in Europe, led to the international recognition of one of the most basic rights: that of persons not to be held in servitude. This was among the first universally established human rights through the Slavery Convention, adopted through the League of Nations in 1926. Prohibition of slavery is enshrined in Article 4 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The Rise of Self-Governance

In Europe and in European colonies throughout the world, progress toward national independence and self-governance based on equality of citizenship gained momentum after the 1848 Revolutions. While these did not overturn the monarchical systems of the major empires, the many national revolutions did help put a final end to serfdom by major states. They also advanced republican rule on the European continent and propelled liberal movements for national independence within empires (such as in Estonia, then under the Russian Empire, and Hungary). Representative governance expanded in Netherlands, France, Germany and other countries (see Country Studies).

This progress accelerated with the end of World War I. Austria, the Baltic States, Czechoslovakia, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Turkey and other republics arose with representative governments after the fall of the Austro-Hungarian, German, Russian and Ottoman empires. The “springtime of nations” provided further impetus to the idea of equal rights for citizens and established a firmer connection between national independence, political freedom and human rights.

The abolition of slavery and serfdom were necessary to advancing self-governance in the 19th century. A frieze on the Monument to the Republic in Paris, France depicting adoption of universal (male) suffrage by the National Assembly on March 8, 1848, which is next to depictions of the Abolition of Feudalism and Slavery, respectively. Creative Commons License. Photo by Teofice.

As well, both before and after World War I, anticolonial movements arose in many parts of the world to press for political participation, democracy, human rights and independence in territories controlled as colonies by imperial powers such as France, the United Kingdom and the United States. These movements accelerated and mostly succeeded after World War II, aided by the adoption of the UN Charter and Universal Declaration of Human Rights (see also Essential Principles).

The Struggle for Universality

The modern concept of human rights as universal developed over time with the expansion of national independence, democracy, equal citizenship and general suffrage. The experience of the United States is instructive.

In the United States, slavery and the restriction of voting rights by race, sex and property ownership limited the fulfillment of equal rights and suffrage promised in the Declaration of Independence. These principles were put in place in the Constitution in the 14th and 15th Amendments that took effect in 1868 and 1870 during the nation’s Second Founding following the Civil War.

Yet, while abolition movements often argued for equality of rights regardless of sex or gender as well as of race, universal suffrage including women took longer. Women only gradually gained the right to vote. The first states to grant it were Wyoming and Utah in 1869. Suffrage for women throughout the United States was achieved finally only in 1919 through the 19th Amendment.

Above, marchers in New York City in 1915 call for women’s suffrage. While adopted in some states starting in 1869 (Wyoming and Utah), women’s suffrage was not achieved nationally until 1919 when the 19th Amendment went into effect. Public Domain. Library of Congress.

As voting rights were expanded for women, they continued to be denied for Black Americans, especially in the South. There, starting in the 1870s, Reconstruction policies were overturned by adherents of white supremacy. Denial of voting and other rights was affirmed by the Supreme Court as it overturned legislation enacted to implement the 14th and 15th amendments. As a result, a system of Jim Crow laws arose that was enforced through a regime of systemic violence that denied Black Americans the most basic rights.

Through the efforts of America’s Civil Rights Movement over more than eighty years, the 14th and 15th amendments ultimately became central as constitutional pillars prohibiting discrimination as the Supreme Court reversed its prior rulings. New legislation ensuring civil rights and voting rights for Black Americans passed in 1964 and 1965 to make America a full democracy for the first time.

Over time, equal rights under the law were extended to women, the LGBTQ+ community, other minorities and disabled persons through legislation and Supreme Court rulings. All of these developments created conditions for greater acceptance of human rights regardless of race, religion, sex, gender and sexual orientation. Similar expansions in the universal applicability of rights have taken place in most democracies, but remains an ongoing pursuit.

The Descent into Totalitarianism

Just as democracy was gaining traction in many parts of the world, Fascist, Communist, militarist and imperial ideologies were taking hold in other parts. In the 1920s and 1930s, fascism and communism seized power in Germany, Italy, Japan, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (which effectively reconstituted the former Russian empire) and other countries. The level of state tyranny in these regimes was unprecedented in the modern world. Not only did these totalitarian regimes institute systems of oppression over all citizens, they targeted whole nationalities and ethnic and religious groups for displacement or extermination (see also Essential Principles).

The challenge to human rights was global: the aim of both fascist and communist regimes was world domination and the total subjugation of societies in the service of totalitarian ideologies.

The challenge to human rights was global: the aim of both fascist and communist regimes was world domination and the total subjugation of societies in the service of totalitarian ideologies. Nazi Germany partnered with Italy and Japan as the Axis powers while each put in place plans for conquest. The Treaty of Non-aggression between Germany and the Soviet Union then divided Europe among these two totalitarian powers to start World War II.

The determined resistance of Britain, the ultimate intervention of the United States, and the resistance of occupied populations and exile armies were decisive in thwarting the Axis plan for mass enslavement and extermination. The Nazis’ ultimate defeat was also due to Hitler’s decision to invade the Soviet Union, ending the Hitler-Stalin partnership and forcing Stalin’s regime to join the Western Allies in the struggle against Nazi Germany. Victory over the Axis Powers, however, was not achieved before 40 to 60 million were killed worldwide, including 6 million Jews in the Holocaust, Hitler’s systematic effort to annihilate European Jewry.

A Foundation for Universality

Soon after the Nazi invasion of the USSR, the United States had extended Lend-Lease to the USSR to provide essential military support. As well, the leaders of the United States and the United Kingdom, Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Winston Churchill, met in August 1941 (even before the US entry into the war) to sign the Atlantic Charter (see Resources). It asserted basic principles to guide the postwar world, most importantly the principles of self-determination, non-aggression, disarmament and freedom.

From the rubble of World War II, there emerged a determination by the US and United Kingdom, working together with leaders of other countries, to entrench the principles of the Atlantic Charter in international law and enforce them in a binding international framework.

From the rubble of World War II, there emerged a determination by the US and United Kingdom, working together with leaders of other countries, to entrench the principles of the Atlantic Charter in international law and enforce them in a binding international framework. The foundation of the new international system, also agreed to by the USSR, was the United Nations. The Charter of the UN was signed on June 26, 1945 by representatives of 51 countries gathered in San Francisco at the United Nations Conference on International Organization. It incorporated the Atlantic Charter’s principles of self-governance, non-aggression, and inviolability of territorial sovereignty in a new world security order.

One of the UN's first tasks was to create the foundation for an international framework for human rights. A nine-member Commission on Human Rights was established in 1946. Eleanor Roosevelt, the head of the US delegation, was elected to chair the Commission. Two years later, after nearly 1,400 votes on the specific wording of the text, the General Assembly, now with 56 members, approved the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) by a vote of 48–0. Eight states — Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Yugoslavia, the USSR and four member countries under its control — abstained. (See Essential Principles for further description of the adoption of the UDHR.)

In addition, the ad hoc Nuremberg and Tokyo International War Crimes Tribunals (as well as some trials held at German concentrations camps) established the principle that state sovereignty did not protect individuals responsible for committing war crimes or crimes against humanity on behalf of a state government. The war crimes tribunals set the foundation for the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, also adopted in 1948. It is the most widely recognized international treaty governing the practice of nation-states.

One of the first tasks of the United Nations was to create an international framework for human rights. Eleanor Roosevelt, shown here in 1947, chaired the UN Human Rights Commission as it drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Public Domain. National Archives and Records Administration.

The Genocide Convention did not prevent governments or armed guerilla movements from carrying out mass murder of national and ethnic groups. In the 1990s, however, the UN did attempt to enforce the Convention with greater intent. The UN Security Council established special international tribunals to prosecute individuals for war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide in former Yugoslavia and Rwanda. Other special tribunals were established for Cambodia, East Timor, Lebanon and Sierra Leone.

These special courts spurred movement toward creation of a permanent International Criminal Court (ICC) through the Treaty of Rome, which came into force in 2002. By 2023, there were 124 signatories to the Rome Statute and indictments had been issued against a total of 51 people with nine convictions. A recent indictment was of Vladimir Putin and Maria Lvova-Belova, President and Commissioner for Children’s Rights, respectively, of the Russian Federation, for the crime of genocide. Specifically, they are charged with the forcible abduction of tens of thousands of Ukrainian children following Russia’s full-scale invasion against Ukraine.

Another important institution in the foundation of international human rights is the International Labor Organization (ILO), which was established in 1919. It is the only surviving institution established in association with the League of Nations and has become a distinct part of the UN system. In setting conditions for labor and freedom of association, the ILO brought worker rights into the larger framework of human rights (see also Freedom of Association).

Universality in Principle and Practice

[M]any UN member states continued to violate human rights on a massive scale with varying justifications. The continued broad scope and extent of such violations is made clear by the annual Freedom in the World survey.

As noted above and in Essential Principles, many UN member states continued to violate human rights on a massive scale with varying justifications. The continued broad scope and extent of such violations is made clear by the annual Freedom in the World survey of Freedom House as well as in Democracy Web’s Country Studies of “not free” and “partly free” countries. In total, Freedom House lists 67 “not free” countries in its 2024 Freedom in the World Survey (an increase of 7 since 2016), together with 59 “partly free” countries where human rights are regularly, if not as systematically, violated. These countries encompass 80 percent of the world’s population (a large increase due to India’s downgrading to “partly free” status).

Still, the assertion of the right of self- governance to be extended to “all peoples” in the Atlantic Charter and UN Charter resulted in decolonization by former imperial powers and the large expansion of nation states. From 56 member states in 1948, the United Nations has grown to 195, a result both decolonization and also the break-up of the Yugoslav Federation and the collapse of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

[T]he standards established by the UDHR and subsequent human rights conventions made universal the principle that human rights should be respected by all states. Even governments violating human rights feel obliged to sign human rights conventions.

At the same time, the UDHR’s assertion that all human beings are "born free and equal in dignity and rights" and its subsequent articles delineating a broad array of freedoms helped to propel a large expansion of human rights internationally. According to Freedom House, the number of “free” countries where human rights are generally respected is now 84 (an increase of 40 countries since the first survey in 1973).

As importantly, the standards established by the UDHR and subsequent human rights conventions made universal the principle that human rights should be respected by all states. Even governments violating human rights feel obliged to sign human rights conventions. In doing so, they place themselves under international scrutiny for their human rights practices.

A Mixed Record for Monitoring

The UN Commission on Human Rights (UNCHR) continued as a permanent UN agency for enforcement of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other conventions on human rights among member states. The effectiveness of the UNCHR was limited since many of its members included blatant human rights violators. For example, the invasions of Hungary and Czechoslovakia by the Soviet Union — among the most blatant violations of both state sovereignty and human rights in the post-war period — were not even deliberated by the commission. Nevertheless, the UNCHR did hold accountable many states, including the Polish People’s Republic following its imposition of martial law in 1981.

In 2005, with many democracies frustrated by its performance, the mandate of the UN Commission on Human Rights was ended and a new UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) was created. However, its membership also includes human rights violators and its deliberations remain politicized. Yet, despite their mixed records, the Commission on Human Rights (UNCHR) and the Human Rights Council (UNHRC) each have carried out essential monitoring of human rights abuses by UN member states and set numerous precedents in upholding international human rights standards.

The 2024 Freedom in the World Map of Freedom shows 84 Free countries but also the uneven respect for human rights (green is Free, beige is Partly Free, and purple is Not Free). There remains a large advance from the first map from 1973, when only 44 countries were Free (countries in white).

In this way, the two bodies have helped to sustain international attention on human rights violations, to provide dissidents and opposition movements greater public legitimacy in their own countries and abroad, and to prod both foreign governments and the UN to impose sanctions and exert other pressure on the authorities in these countries to adhere to human rights standards.

For example, the UN Human Rights Council established Commissions of Inquiry for Syria and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. These commissions have issued comprehensive reports on human rights violations that are the basis for resolutions and referrals for action by the UN Security Council and the International Criminal Court (see Resources in the Syria and North Korea Country Studies for links to the reports). Absent these reports, there would be no basis for the UN to take action against these egregious human rights violators.

Freedom House, founded in 1941 under the bipartisan leadership of Eleanor Roosevelt and Wendell Wilkie (the Republican candidate for president in 1940 defeated by Eleanor Roosevelt’s husband) was among the first organizations to generally advocate for human rights worldwide and helped to develop the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Today, the principle of the universality of human rights is reflected in the many human rights organizations that have been organized in the US, Europe and throughout the world, including in many countries where human rights are being denied. Human rights defenders continue to risk prison and other repression for their work.

The content on this page was last updated on .