Introduction

[F]reedom of expression is . . . one of the basic foundations of liberty — an essential principle without which democracy could not exist.

Freedom of expression is considered among the most fundamental of all freedoms. While one cannot rate one freedom over another, freedom of expression is undoubtedly one of the basic foundations of liberty — an essential principle without which democracy could not exist.

In a democracy, freedom of expression is essential for free and fair elections. The citizenry relies on the free flow of information and opinion, including about the functioning of their government, in order to decide for whom to vote as their representatives. Freedom of expression offers all political parties, whether in the majority or the minority, equal chances to be heard and so gives minority parties the opportunity to become the majority by means of persuasion. When the state restricts the flow of information or political discussion through censorship or control of media outlets, there can be no free or fair elections.

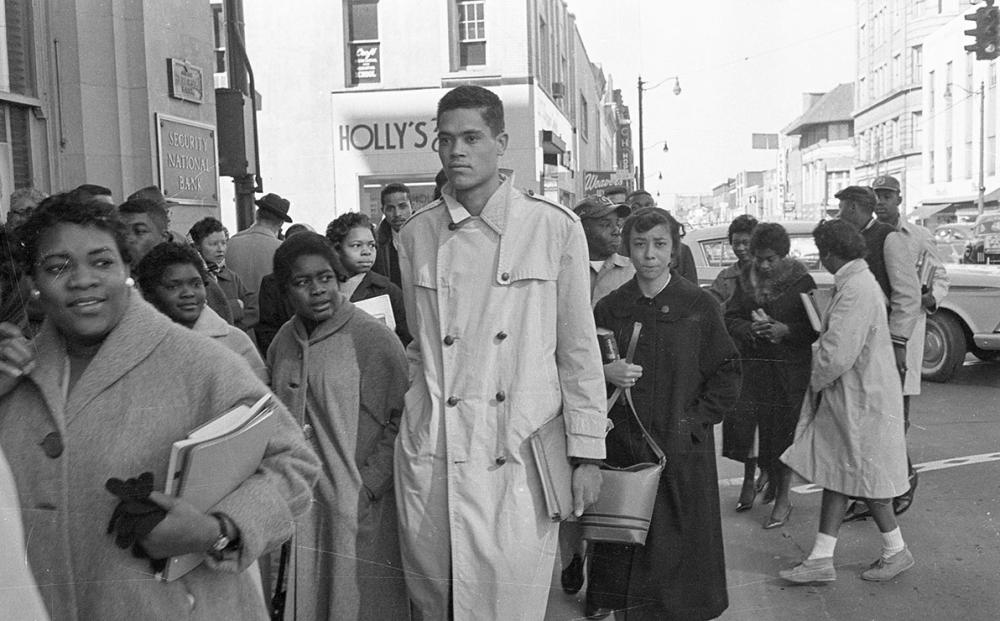

Freedom of expression is both an individual right and a collective right to voice opinions in common. Above, a 1960 demonstration outside Woolworth’s in Greensboro, North Carolina in support of the student sit-in demanding to integrate lunch counters and store facilities.

Freedom of expression is also essential for civic life generally and the ability of citizens to form political parties, trade unions and other organizations that protect their rights and interests. Without freedom of expression, freedom of association and freedom of religion are also necessarily restricted — as are other essential principles of democracy such as minority rights, accountability and transparency, economic freedom, rule of law and academic freedom.

Meaning and Scope

Freedom of expression means that the government may not unduly restrict the publishing of books, newspapers or other printed materials, the broadcast of media, or the advocacy of political views. But the term has larger meaning. Freedom of expression also encompasses freedom of thought, conscience, cultural expression and free inquiry.

Freedom of expression means that the government may not unduly restrict the publishing of books, newspapers or other printed materials, the broadcast of media, or the advocacy of political views.

Freedom of expression guarantees everyone's right to speak in public and to write openly, including to criticize the injustices, misdeeds and incompetence of the government or its representatives — all without state interference or fear of state reprisal. This includes the right to inform the public, to offer opinions and to advocate change, including to change the government. Freedom of expression is not just an individual right but a collective right of the people to voice opinions in common and so protects expression of organizations representing specific interests of the people.

Freedom of expression is called by some political theorists a “negative freedom” or right, meaning something that the state may not take away. The Bill of Rights frames the right as one that Congress may not “abridge” by any law. (Negative freedoms are counterposed to “positive freedoms,” or public goods that the government must provide, such as education or health care.)

While freedom of expression is something to be safeguarded by the state, and not infringed or abridged, the right extends to non-state institutions. Private institutions may limit speech and enforce codes of behavior within and among themselves, but free expression is considered a necessary part of democratic culture and thus a right to be respected and protected generally. This is the case especially in institutions where freedom of expression is necessary to fulfill their purposes, such as colleges and universities.

From Censorship to Universal Standard

Until the 20th century, censorship—not freedom of expression—was the practice of most states and institutions. Autocracies and quasi-state structures like the Catholic Church frequently exiled, excommunicated, imprisoned, tortured or even killed critics. Written and artistic works were censored. For rulers and religious structures, it was essential to maintain supreme authority. This required control over what people could read and think.

Until the 20th century, censorship . . . was the practice of most states and institutions. Autocracies and quasi-state structures like the Catholic Church frequently exiled, excommunicated, imprisoned, tortured or even killed critics. Written and artistic works were censored.

From ancient empires to the Star Chamber in Britain and the Vatican’s centuries-long Index of Prohibited Books, there are many examples of formal censorship regimes. In history, intellectuals, artists and public citizens would test the limits of accepted speech, often resulting in harsh consequences.

Three key developments expanded the realm of free expression and thought, especially in Europe and the Western Hemisphere. The first was the struggle against licensing requirements in Great Britain in the 17th century. The second was the adoption of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen by the French National Assembly in 1789. The third was adoption of the American Bill of Rights in 1791. Each established freedom of expression as a right that governments should not restrict outside limits set in law for libel and slander (see also History).

Among key historical developments expanding the realm of free expression was adoption of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen during the 1789 French Revolution. Above, a copy of the Declaration. Creative Commons. Imprint by Frère Périsse.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, there was a broad expansion of transmitting news and information and publishing books to a mass audience in Europe, the Western Hemisphere and other parts of the world where representative government took hold. Mass distribution of newspapers, books and other printed material was done in increasingly free environments. Religious institutions still acted to constrict free expression and cultural freedom, but in countries with democracies, governments allowed the realms of publishing, art and thought to expand.

The rise of totalitarian regimes in the first half of the 20th century, such as Adolf Hitler's Germany and Joseph Stalin's Soviet Union, reversed this broad trend. The Nazi practice of book-burnings and destruction of libraries and the Soviet Union’s mass purges and total censorship brought into stark clarity the importance of freedom of expression. In such regimes, the state not only repressed any expression of criticism by citizens but also controlled all media to impose conformity of thought and opinion.

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

Article 19, Universal Declaration of Human Rights

After the defeat of Nazi Germany and the Axis Powers in World War II, the United States and the United Kingdom acted to build a general international consensus on human rights. The adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was considered foundational to achieving an international system of security and peace. Freedom of expression is central to that system. Article 19 of the UDHR states:

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

Totalitarian regimes continued to exist, including the Soviet Union, as did other types of dictatorships that mirrored their practices. Yet, freedom of expression was accepted internationally as an essential principle of human liberty. Within democracies, the general trend was to expand free expression and it became a key tool for achieving long-needed democratic reforms, as shown, for example, by the Civil Rights Movement in the United States. Within dictatorships, freedom of expression was a necessary demand to achieve freedom, as with the Solidarity free trade union movement in Poland (see Country Study).

Freedom of Expression in Democracies

The theory and even most practices involving freedom of expression are clear. Media, individual citizens, organizations, politicians, lobbyists, corporations and trade unions all have the general right to speak or publish information, to express opinions and views and to try to influence the voting public and public policy. The state should not limit that right unnecessarily, whether through licensing requirements or restricting access to various physical or virtual methods of dissemination. Only the abuse of expression, such as libel and slander, face restrictions where citizens may seek redress in courts of law.

In democracies, there are ongoing debates on the limits of protest. Above, a peaceful rally in London in 2022 to “Kill the Bill” aimed at placing restrictions on demonstrations. Public Domain.

Yet, as with all freedoms, there are ongoing debates on whether the state can or should place certain limits on individual or group expression.

- Should a democracy have laws to protect against individuals or groups inciting hatred or that advocate for the overthrow of the government?

- To what degree should the publishing of sensitive national security information be restricted and how does the state decide what is sensitive?

- Should spending on political campaigns and political advocacy be limited or should individuals, groups or corporations be able to spend unlimited amounts of money for such purposes?

- Do bans on religious expression in state settings (as in France) violate rights of free expression and freedom of religion or uphold separation of church and state?

- Should print distribution or broadcast of explicit sexual material be restricted?

In all countries, there are laws against printing or stating in public false or defamatory information that intentionally damages an individual’s, a group’s or a business’s reputation. Most countries limit distribution of explicit sexual material to one degree or another. There are laws to protect intellectual property and prohibit dissemination of information harmful to national security. Most democratic countries limit spending on political campaigns and political lobbying to maintain a level playing field for candidates and prevent the buying of power or influence by wealthy interests.

Still, the limits and propriety of free expression vary. For example, the United States — at least until recently — expanded the realm of free expression and has fewer limits on it, including for slander and libel, hateful speech and political spending on elections and lobbying (see History). In this last category, most democracies limit political spending to maintain an even playing field for elections and political influence and to prevent corporations and the wealthy from having unfair influence over elections and public policy. As well, Germany, reflecting its totalitarian history, has greater restrictions, such as prohibiting hate speech and the propagation of Nazi ideology and symbols. It also bars extremist parties espousing Nazism (see Country Study).

France and Netherlands (the Country Study in this section) also have limits on hate speech and make it a crime to deny both the Holocaust and the genocide of Armenians in 1915–16. Until 2013, France maintained a law against insulting the president (the law was revoked after the European Court of Human Rights ruled it a violation of the UDHR).

[F]ree speech advocates and organizations seek to minimize state prohibitions, arguing that any restrictions on free expression lead to more restrictions.

As with other essential principles, there are no absolute answers to issues of free expression. In democracies, free speech advocates and organizations seek to minimize state prohibitions, arguing that any restrictions on free expression lead to more restrictions. (See, for example, “The Meddler’s Itch,” by Rony Koven in Resources.) On the other hand, those seeking to ensure free and fair elections consider certain limits on speech as necessary or desirable, such as barring the purposeful spreading of false information about voting information or limiting spending for political campaigns and advocacy.

Debates and controversies will continue where any restrictions are applied. Recently, there has been new debate about the limits of speech and civil disobedience, especially at public and private universities, in relation to harmful or hateful speech and protests over the Israel-Gaza war.

But it is precisely the existence of open and free debates (and the use of the rule of law to help resolve formal disputes) that offers a clear distinction between democracy and dictatorship. Where government leaders in electoral democracies act to restrict that debate and exert greater control of media or repress speech (as recently in Philippines and Poland, among others), it is a sign of a country moving towards authoritarianism.

Free Expression in Dictatorships

Totalitarian regimes like the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China continued to exist after adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. These and many other types of dictatorships egregiously violate freedom of expression through censorship and state control over media, book publishing and educational and cultural institutions.

The essential principle for dictatorships is the maintenance of political power. Free expression is considered a danger since the open dissemination of information about corruption, opinions critical of the government or the advocacy of democratic rights undermines the state’s legitimacy to rule.

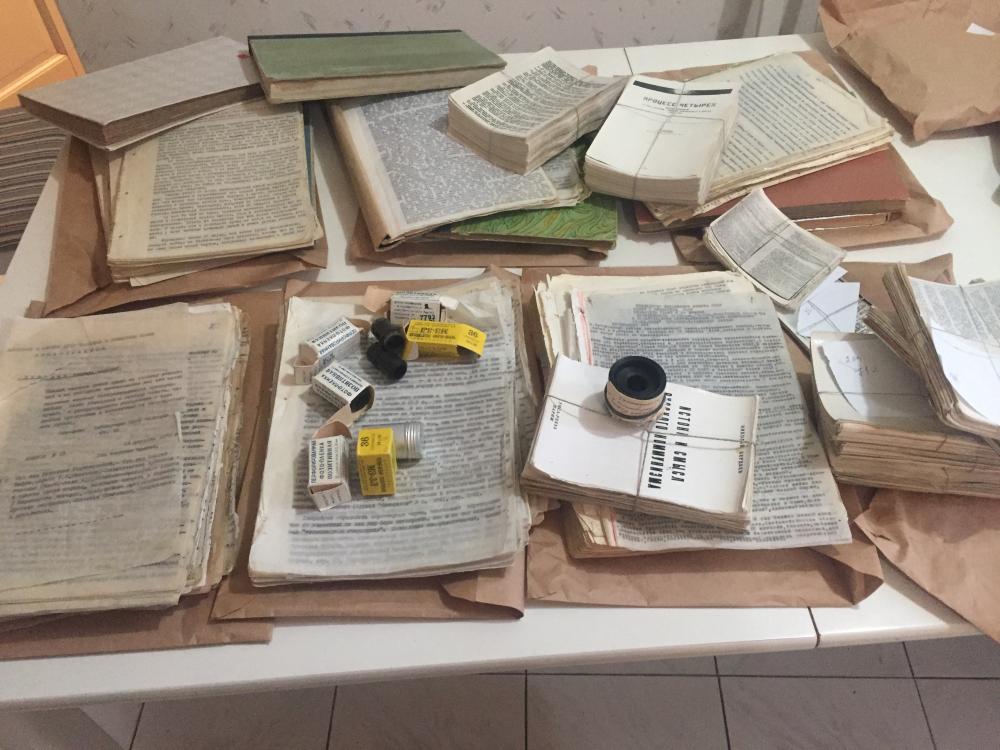

Samizdat (self-publishing) in the Soviet Union is an example of how citizens have challenged censorship regimes in dictatorships. Above, examples of samizdat literature in both print and photo negatives. Creative Commons. Photo by Nkrita.

The logic of censorship leads to repressing all independent expression and thought. In the Soviet Union, for example, it led to a comprehensive censorship regime in which anything published in print as well as text for broadcast had to be submitted for approval to the General Directorate for the Protection of State Secrets in the Press (known by its acronym Glavlit). The Communist Party’s ideological department dictated what could be approved.

Within dictatorships, citizens’ movements for free expression arose to challenge censorship regimes, such as samizdat, or self, publishing in the Soviet Union and the Democracy Wall and Charter 08 movements in the People’s Republic of China (see Country Study in this section). In asserting the right to free expression, these movements pointed to Article 19 in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international guarantees for intellectual, academic and cultural freedoms. As in prior centuries, intellectuals, writers and activists would test the boundaries of state controls on speech and publishing. Despite severe consequences, they continued such challenges because they knew free expression helped build movements for change and expand the borders of democracy (see also History).

New Challenges

Today, debates in democracies over free expression described above are complicated by new political and technological challenges.

In many democracies, “populist” political parties use extremist rhetoric and false claims to stoke fears of foreign threats to the citizenry (even to their countries’ “existence” and “civilization”). In some (such as France and Netherlands), populist parties seriously contend for power. In others, such as Israel, Poland and the United States, such parties achieved power to adopt harsh anti-immigrant and anti-democratic policies. In each case, the parties relied on politicized state or private media that rejects fact-based journalism.

Populist leaders that gained power in some countries (such as Hungary, Philippines and Turkey) succeeded in shutting down or taking over critical print and digital media outlets, imprisoned or fined independent journalists and asserted greater control over print and broadcast media. Such control of media is a key means to skew elections in their favor and ensure their authoritarian-style rule.

Right-wing populist leaders in some countries succeed in restricting free expression to preserve power. Above, Hungarian leader Viktor Orban in 2015. His government has effective control over media through a licensing board. Creative Commons. Photo by European People’s Party.

In the midst of these political developments, new digital technologies and means of disseminating information, such as digital media platforms and social media, have supplemented and even supplanted print and broadcast media. At first, this was seen as a broad expansion of free expression. Over time, these new platforms are seen less as a means of fostering the free exchange of information and more as a vehicle for disinformation and political manipulation by “populist” parties and authoritarian-minded leaders.

Meanwhile, dictatorships like the People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation developed their own sophisticated social media and digital platforms together with comprehensive censorship regimes to control online posts and what information citizens see. China has even instituted “social credit” monitoring of the entire population where individuals are credited or discredited by their political views and behavior. The Chinese and Russian governments, along with those of Iran and North Korea, also developed means to launch cyber-attacks and to disseminate mis- and disinformation to sow discord within democracies.

New Challenges (cont.)

Does the state have a responsibility to regulate broadcast or social media companies in order to limit the spread of disinformation affecting free and fair elections? What responsibility do broadcast and social media companies have in regulating themselves or from being used by dictatorships to manipulate elections within their own countries (as the Russian Federation has done in Western democracies) or to incite genocide (as the military regime in Myanmar did in directing violence against the Rohingya minority group)? In democracies, there are varied and unclear responses to these questions at the moment in legal cases before the Supreme Court (see articles by David Cole in Resources).

As well, government regulation of broadcast media previously sought to maintain balance in reporting but the United States removed its “fairness doctrine” in 1988. The European Union maintains policies to foster fairness and objectivity in the news, but it also now allows greater freedom in licensing. This has led to a common phenomenon in democracies: billionaires and mega corporations gaining control of print, broadcast and social media empires to skew political debate in an anti-democratic fashion or to favor business over labor.

In this new media framework, there remain many issues regarding how democracies navigate between free expression principles and other essential principles (like free and fair elections and economic freedom). Yet, what the history of the last 250 years has shown is that freedom of expression is a bedrock of democracy (see History).

The content on this page was last updated on .